I’ve been researching my family history, which I knew was nautical themed, but never quite sure exactly how. With Parents, Grandparents, aged Aunts and Uncles also now long deceased, it is impossible to obtain detailed answers. However, the internet can indeed sometimes be a wonderful thing. How many hours it takes devoted netizens to archive, record and place available, online, sometimes the most trivial and esoteric data never quite fails to amaze me. Researching the Devonshire-Ellis’s was a bit of a task – the name is not always used amongst family members, and is carried down via the eldest son. On occasion, it’s been dropped from use altogether – fear of being cast as aristocrats or as wealthy was not such a desirable thing in post war Britain.

Fortunes lost were also considered to be a taboo subject, although there was always something lurking in the background when I grew up, occasional mentions of old family riches and some sense of importance. Yet it remained hidden, possibly because in shame, my own Father apparently gambled away his inheritance and the subject was best forgotten about, to be mentioned to no-one, least of all me, the son and heir. But as Morrissey sang, it was to prove to be the son and heir to nothing in particular.

Curiosity though is a hard totem to shake off. Looking for clues about my Grandfather – who had died eight years before I was born, and who I knew had been a Royal Naval Officer, began to yield clues. One website mentioned him as a small, single apple, part of another family tree, and provided his Father’s name, and so on. Reaching back, it lead to John Devonshire-Ellis, casually listed as being “Managing Director of the John Brown & Co, of Sheffield†in the 1850’s. That proved to be quite a lead. While “John Brown†is a fairly common name, the Sheffield link was telling – and company information and records were scattered throughout the internet. Sheffield was the home of British steel, and John Brown & Co one of the more dynamic. John Devonshire-Ellis, originally brought in as a Partner of the actual John Brown, grew weary of the founders apparent willingness to take company money and property as his own – which can remain a common failing amongst entreprenuers, especially when partners are brought in. Devonshire-Ellis must have been a resolute man, as Brown was eventually dismissed, and his shares bought out. He was a wealthy man of the day, but sadly his other ventures, and his apparent weakness of living beyond his means saw him eventually die in poverty. It was a situation that Devonshire-Ellis noted in Brown’s obituary, caused him ‘much sorrow’.

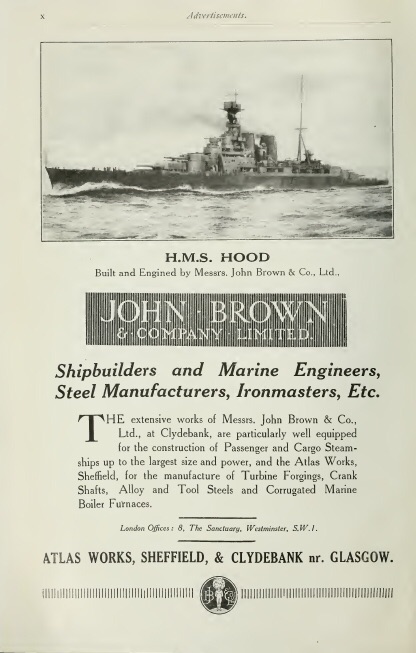

Meanwhile, under Devonshire-Ellis’s management, the John Brown Company began to invest, innovate and improve. Noting, in 1855 that French warships were being clad in steel, he invented a method of effectively ‘double-glazing’ steel sheets and sold the fact he could do so to the British Royal Navy. In a time of increasing European tension, Britain was about to boost its Naval capabilities. Warships were ordered, trialed and shot at with cannon. Devonshire-Ellis’s steel plating held firm, and the firm bought out existing shipbuilding operations in Clyde, Scotland in order to provide the facilities to attach the Sheffield made plate to ships.

John Brown & Co Shipyards, Clyde

With five children growing up fast, John Devonshire-Ellis also had a ready supply of trusted family talent to enter what was now the family business. Arthur, the eldest son, became company accountant. As capital grew from 10,000 Pounds and a workforce of 250 to Three Million Pounds and a workforce of 16,000 in the space of eight years, his financial management proved the bedrock upon which his younger brothers, both trained as engineers, could further develop the company. With Europe becoming increasing tense, John Brown & Co was now providing 30% of all ships for the Royal Navy, including the massive Dreadnoughts. Wartime was to prove a boost for the business. Peacetime, though, no less so. The 1920’s and 30’s were the Golden Age of Ocean Liners, Atlantic Crossings, and American money crossing from New York to Europe. John Brown made many of those ships and where a preferred supplier to Cunard. The Queen Mary, Luistania, Mauretania, and eventually Queen Elizabeth were all John Brown ships, the fastest, biggest and most opulent afloat. Competing with German shipyards, an announcement was made that a new German Ocean Liner was to be the world’s longest. Charles Ellis, second son of John, by then Managing Director, bided his time. Just when the Germans’ had laid down their keel, meaning no structural alterations could be made, he countered, in partnership again with Cunard, that the world’s longest liner (Luistania) would in fact be built at Clyde, and be a British achievement.

RMS Queen Mary

The Queen Mary meanwhile, achieved the fastest Atlantic Ocean crossing, both eastwards and the more difficult westwards crossing. That earned it the unofficial title of the Blue Riband. Upon being notified of the award, Charles Ellis apparently stated “We build the best and fastest liners, but Ocean racing is not our business†and refused to accept the award, which he saw as somewhat of an affectation.

That reluctance to court publicity ran throughout the family, with business aptitude and a desire to be low key at the forefront of attitudes. These men were engineers, not celebrities. John Brown & Co also differed from their competitors as they would allow technology transfer to take place and permit their designs to be built in foreign shipyards under John Brown supervision. This meant that mainly naval vessels for the Italian, Japanese and Russian Governments were built by John Brown in those countries shipyards rather than at Clyde. It may well be the case then that in Russia’s disasterous war with Japan, John Brown Ships were bombing each other.

The company received another boost during World War Two, with many ships being built and deployed. But it was to be the swansong. Post war, with no money in Britain, and a Labour Government introducing both Unions, and Death Duties, the John Brown company, and fortunes of the Devonshire-Ellis’s began to run into trouble. Soaring employee overheads, dwindling orders and political interference, coupled with a lack of new family members on the board – several Devonshire-Ellis’s and Ellis’s died during World Wars One & Two – meant the family lost control of the company to what effectively were Civil Servants. There was still time for the business to design and build the Royal Yacht Britannia and the Queen Elizabeth 2 Ocean Liner under previous  Devonshire-Ellis plans and blueprints, but the QEII was the last of the great ships to leave the Clyde shipyards. Today even the QEII is no more, while the successor Queen Mary II was completed in   The era of British shipbuilding came to an end, and ultimately moved overseas.

RMS Queen Elizabeth II

For the family though, it had effectively been seventy glorious years of building the best, biggest and fastest ships the world has ever seen.

A complete overview of the Devonshire-Ellis family history, including John Brown & Company, with details of family members, and the ships built by them, has been created and placed online by me here: www.devonshireellis.com