The Arctic regions have fascinated me for years, starting with visits to Tromso and then to Svalbard, the closest permanently inhabited place to the North Pole. Arctic discovery was originally undertaken by the British, Danish and Norwegian explorers, looking both for the elusive Northern trade route to Asia, and also in the whaling industry. Most of the Russian influence on the Arctic remained remote, even though the bulk of the Arctic circle is Russian territory, until the Soviet era.

Kola Bay however was well known, at least amongst the European explorers, with a scattering of Russian trappers and fishermen eking out a harsh existence all the way along the Arctic coast. It wasn’t until the era of Catherine the Great that Murmansk was even given the status of a town, and it didn’t appear on maps until the beginning of the last century.

Today, Murmansk is the largest city in the Arctic Circle, including settlements in Canada and the United States. Getting there is a simple 90-minute flight from St.Petersburg. It is the capital city of the Arctic, and has been a strategic, Arctic warm water port since it was founded. Originally consisting of traditional wooden buildings, Murmansk assumed some importance during World War Two as a supply chain to the Red Army fighting off German advances in Scandinavia, who wanted access to northern Russia’s energy reserves. With Norway overrun by the Nazi’s, Murmansk suffered terribly with bombings and arial attacks and was mostly destroyed. But the Soviet era, Red Army sacrifices made here helped fend the Nazi’s off and the city was never captured. During the Cold War era, Murmansk developed into a base for the USSR nuclear submarine fleet and was a closed city.

Today, it is a base for the Russian Northern Sea Route Icebreaker fleet, which is now developing and assists shipping from Northern Europe (mostly Russia these days) through to China and beyond. Russia has the world’s only nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet, and the original vessel, named Lenin, dating back to the 1950’s is now a tourism attraction.

But I am here for a safari. An Arctic Ocean safari. This far north, the White Nights remain during the midsummer, and Murmansk remains bright, even at two in the morning. Pictured is the tallest building in the entire Arctic Circle, the appropriately-named ‘Arktika Hotel’. To the left is a huge, inflatable whale. This photo was taken at 2am.

Murmansk has an excellent variety of restaurants, with a unique range of dishes – Arctic seafood is superb, while the Russian tundra region provides plenty of game. Therefore, it is standard to find both aged venison, elk, and bear, together with fresh halibut, salmon and cod on the same menu. Naturally, I indulge…

Touring Kola Bay, the size of Murmansk – it remains a relatively small city – becomes apparent – it has a population of just 270,000, with most of the activity surrounding the port – it remains an active seaport. Parts of Murmansk can seem a little grubby, but it is a working port, although the downtown area is typical, Russian soviet-styled Georgian buildings.

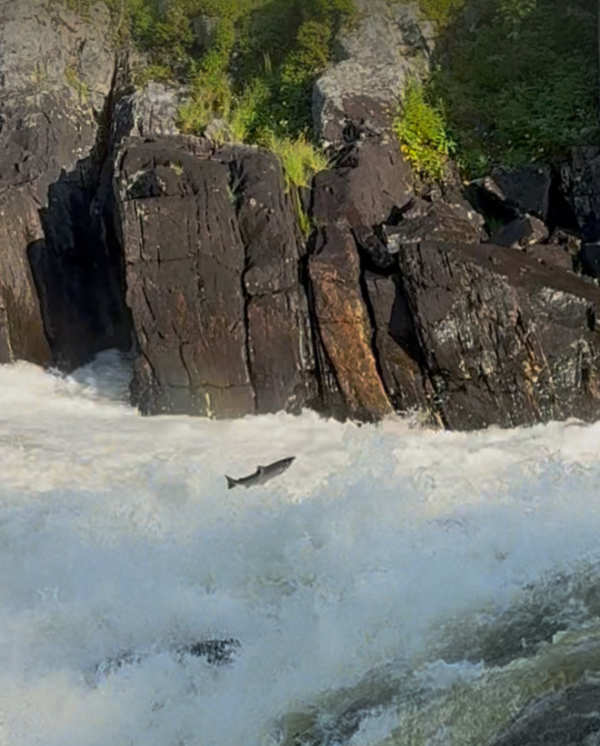

Heading inland, deeper into the Tundra, I want to explore the rivers – I have with me an original copy of the 1901 book “Three Summers Among The Birds Of Russian Lapland” by Henry J. Pearson, who travelled this region extensively between 1898-1901, and want to explore some the areas he visited. I am well rewarded – I trek up the Tuloma River – which is stunningly beautiful, and come across several waterfalls. I even take a quick dip. Later, I watch the Atlantic salmon try to reach their breeding grounds by jumping up the falls.

The next day, I am travelling further north-west, to Teriberka, which became well known due to its portrayal in the Russian film ‘Leviathan’, although the locals weren’t ultimately happy about it as it wasn’t a kindly, welcoming story (although it is worth viewing). This is a four hour journey across the Arctic Tundra, with the road sometimes closed during the winter due to drifting snow. I have visited before, in the deep winter, to see the northern lights, but this is an entirely different landscape in the summer months. The Tundra is a specific ecological Arctic zone, characterised by undulating hills, many lakes, and occasional rivers.

Teriberka itself is a small fishing port, with a quaint harbour, and has a small, developing tourism industry with an array of wooden cabins set about 50 meters from the beach along one coastline, which is where I stay.

Teriberka is also home to a ‘ship graveyard’ which contains the remains of 1930’s era, wooden passenger and haulage boats. It’s a reminder of its nautical past – some of the degrading wrecks here will have originally dated from the 1890’s.

I am here though for an Arctic safari, with no real agenda to see anything specific – just nature as she decides to reveal herself. A local, good quality boat and skipper can be had for about US$60 for three hours, which is enough, as it can get chilly with the Arctic Ocean breeze coming off the surface.

The Bering Sea here is a huge migratory and breeding ground for numerous animals, and is famous for its whales and dolphins, although different species are more common at certain times of year. It’s the height of summer, and Kittiwakes, Lesser Black-Backed, Greater Black-Backed, Common, Herring Gulls and Arctic Skuas are all present, with the Kittiwakes in huge colonies.

As we head out, I can spot several other sea birds – Scoter, Long Tailed Duck, Scaup, until the skipper pulls in close to a headland. There, sunbathing on the rocks, are three very fat Common Seals.

I deduce that the larger is the dominant male, while other seal heads begin popping up from the sea at a distance from the boat. They are completely chilled out, but I am mindful that these creatures can weigh up to 170 kg.

We head off to leave them in peace, and almost immediately come across a large pod of Bottleneck Dolphins, feeding in a fast, 1km circular route that means we must constantly change our position to keep up with them. These Dolphins don’t jump out of the water, but they are very fast and very large – an adult can weigh up to 650kg. These are huge animals. They also have erect, curved dorsal fins, which to the uninitiated could cause one to think ‘Shark!’ – but dolphins fins are sabre like, whereas most shark fins are distinct triangles.

Then, as we head back to the harbour, an unexpected sighting, and quite distinctive – Beluga Whales! These are relatively easy to spot as they are a pure white colour, and stand out against the dark of the Ocean. Like most Dolphins, they do not jump, although they can be inquisitive and sometimes put their heads out of the water to take a look around. I don’t like seeing large animals in aquariums or zoos, and I can see how in their element they are. At least two calves are with this pod, as they two busy themselves with hunting, mainly for the numerous varieties of Arctic fish. I attach an internet-sourced image to see the complete animal. Of course, these are mammals, so must come up to breathe. In the winter, when the ocean freezes over, Polar Bears wait by their ice air holes, waiting for the Beluga to take a quick breather…

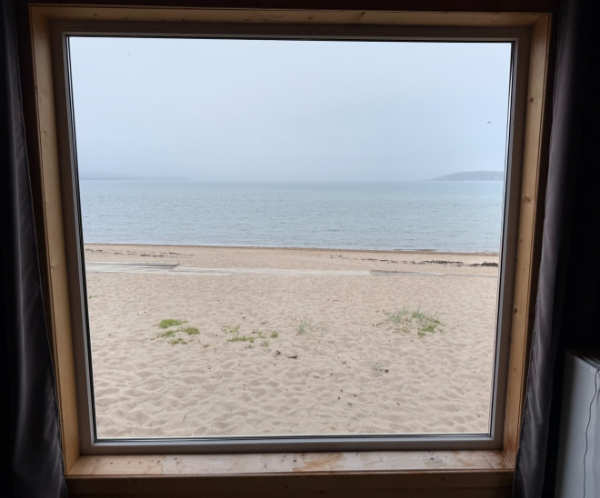

That evening, back at the cabin, it remains light, and I have a fantastic view over the Teriberka bay. At 1am, I spot a large group of Mergansers, a saw-billed duck, gradually move towards the shore. There, as the small waves break against the beach, they paddle furiously along, scooping up whatever small sea creature may have been momentarily confused by the waves crashing on the shore. I’ve never seen such behaviour before, and Pearson doesn’t mention it in his book either. The Arctic Ocean leaves me feel like I’ve experienced something just a little bit extra-special.

The next morning, I visit a local Sami shamen, whose juvenile Barn owl, Elisa, tells my fortune. The Sami are the indigenous inhabitants of the region and can be found throughout Norway and Russia. Most are Reindeer herders, and as Reindeer are migratory animals, that meant that back in the day, they used to follow herds about at the top of the world. Interestingly, in the Tuva region of Russia and in northern Mongolia, there are also shamens, who I have also visited with before, around the Lake Khovsgol region, and further north-west to the Russian border. What’s interesting about the Sami, and the Mongolian shamens, is that they share numerous cultural behavioural traits, such as living in Uvs a type of wigwam, while some of their physical appearances can also be similar. My fortune is good, Elisa informs me, as I am also treated to a traditional reindeer moss snack and cups of local herbal tea and incense. I have the feeling that being blessed by an Owl is a very fortunate sign.